BY SUSAN GANDHI SCHULTZ

One of the main challenges my clients who do business internationally face? Getting balanced and open input in meetings that involve diverse countries or cultures.

WHY IS IT CHALLENGING TO GET SOME CULTURES TO SPEAK UP DURING MEETINGS?

In a hierarchical culture, it is the senior most who speaks first, and the most. Need for inclusive discussions, fear of making a mistake, or causing loss of face by disagreeing with others, are other reasons that prevent participation.

THUS, PROVIDING MULTIPLE AVENUES TO ENCOURAGE PARTICIPATION, IS VITAL TO FACILITATING EFFECTIVE MULTICULTURAL MEETINGS.

-

Small Group Discussions.

Avoid asking a question and expecting individuals to speak up right away. Instead, give people a few minutes to discuss among themselves, or in their remote locations, before sharing their ideas.

This addresses the issues hierarchy, inclusion, and face, as well as language differences.

-

Round Robin.

For meetings with small numbers of participants, ask each individual for their input, but with the caveat that they “can pass”.

-

Open Ended Questions

Saying “no” or “I don’t know” can be challenging for face oriented cultures.

Thus avoid asking questions that force a “yes” or “no” answer. Instead of asking, “Do you have any questions?”, you could say, “Please take 5 minutes to think about questions you may have.”

-

Written Text

As much as possible, display written text versus only verbally asking questions. Some cultures may hesitate to ask for clarifications if they cannot understand your spoken words.

-

Frequent Breaks

Have 10-15 minute breaks every 60-75 minutes. Some participants may prefer to share their thoughts in private versus public, so be available for part of the break time. And after the meeting too.

-

Call on an Individual?

The complexity of hierarchy, face, etc. can make this a risky option so use it only when you are certain it is appropriate to do so.

So when facilitating international, multicultural or cross-border meetings, keep your focus on your key objective: that of getting input. And then adapt to the cultures involved.

As an Intercultural Consultant, for over 25 years Susan Gandhi Schultz has worked with organizations to successfully develop global leaders, create effective global multi-cultural teams, guide expatriates, and build a cross-culturally inclusive workplace. She is currently authoring a book on Working Effectively Across Cultures, in which she shares insights from nationals from 30 countries on how to succeed when working with their cultures.

As an Intercultural Consultant, for over 25 years Susan Gandhi Schultz has worked with organizations to successfully develop global leaders, create effective global multi-cultural teams, guide expatriates, and build a cross-culturally inclusive workplace. She is currently authoring a book on Working Effectively Across Cultures, in which she shares insights from nationals from 30 countries on how to succeed when working with their cultures.

As an Intercultural Consultant, for over 25 years Susan Gandhi Schultz has worked with organizations to successfully develop global leaders, create effective global multi-cultural teams, guide expatriates, and build a cross-culturally inclusive workplace. She is currently authoring a book on Working Effectively Across Cultures, in which she shares insights from nationals from 30 countries on how to succeed when working with their cultures.

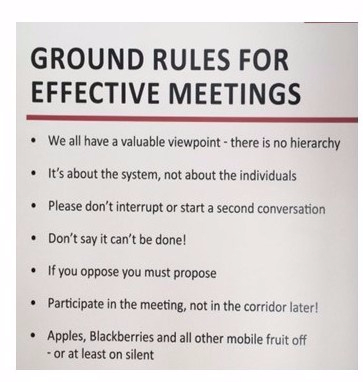

As a consultant, I facilitate many multi-cultural trainings and these ground rules cannot always be applied. For some cultures, open participation is not the norm, and public disagreement is disrespectful as it can cause loss of face. In fact, “corridor or coffee room chats” is where much of the discussion is done. For others, discussions with team members are important; hence the side-bars. The issue is not the rules themselves, but that they are determined without considering cultural differences.

As a consultant, I facilitate many multi-cultural trainings and these ground rules cannot always be applied. For some cultures, open participation is not the norm, and public disagreement is disrespectful as it can cause loss of face. In fact, “corridor or coffee room chats” is where much of the discussion is done. For others, discussions with team members are important; hence the side-bars. The issue is not the rules themselves, but that they are determined without considering cultural differences.

This story is not a true event, but how often do we believe we are right when we need to ask questions?!

This story is not a true event, but how often do we believe we are right when we need to ask questions?!

Linkedin

Linkedin

Connect:

Connect:

Linkedin

Linkedin